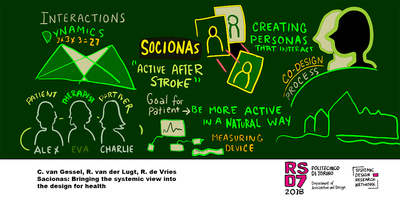

Socionas: Bringing the systemic view into the design for health and sustainability

Van Gessel, Christa, Van der Lugt, Remko and De Vries, Rosa (2018) Socionas: Bringing the systemic view into the design for health and sustainability. In: Proceedings of RSD7, Relating Systems Thinking and Design 7, 23-26 Oct 2018, Turin, Italy.

Preview |

Text

VanGessel_Slides_2018.pdf Download (27MB) | Preview |

![VanGessel_MM_2018.jpg [thumbnail of VanGessel_MM_2018.jpg]](https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/2762/2.hassmallThumbnailVersion/VanGessel_MM_2018.jpg)  Preview |

Image

VanGessel_MM_2018.jpg Download (987kB) | Preview |

Abstract

Introduction

One of the key ingredients of a designerly approach is to stay connected to the real life, human perspective, even if the design process calls for high levels of abstraction and modelling. Designers design well with pictures/stories of real people in their heads, rather than with statistics (Sleeswijk Visser et al, 2005). Persona’s (e.g. Cooper, 1999; Pruitt & Adlin, 2006) have become a commonly used method across the fields of design: using rich narratives of constructed people, based on real user data as a compass in the design process.

Even though this is a valuable approach, the human-centeredness can also be a pitfall in designing within complex situations, as the focus on the individual experience of people can lead to underconceptualizing the problem and, and in-turn sub-optimal ‘quick-fix’ solutions. (Jones, 2013).

Within design for health, a lot of attention has been given to behaviour change, and behavioural design (e.g. Fogg, 2009, Lockton, 2010, Cialdini,2015, Hermsen et al, 2016), which focus on the individual (oftentimes the patient). Dynamics within the care network around the patient are referred to as social context. However, these dynamics between people strongly influence behaviours of people within healthcare, and designerly interventions directed to break these patterns could be much more effective than bombarding individuals with persuasive interventions.

Besides an awareness of processes and dynamics involved in a healthcare, and awareness of the larger system at hand, we noticed that both designers and healthcare workers could benefit from a sensitivity towards systemic patterns and dynamics in the small, to enable them to sense, interpret and act based on this. This led to the following research question: In what ways can designers get insight in the hidden dynamics in care systems and how can they maintain and include these insights throughout the co-design process?

Socionas

In this paper we present socionas as a tool to aid designers to incorporate the systemic view into the design process. Postma (2012) first coined the term socionas in her search for a method that allows for designing for person-person-product interaction, as she found that tools for user-product interaction did not attend sufficiently to the social consequences of interacting with products. Her approach is based on Activity Theory (Engeström, 1987) and Stanislavsky’s System (1961) as anchoring theories in order to develop a method for designers to empathize with their users and the social context in which they operate.

We adopt the term socionas, but use them in a slightly different way, referring to a way to capture variations in prototypical dynamics in social systems (such as care networks) and enable designers to work with the systemic level, while not losing sight of the individual. Basically, a sociona consists of a visual description of the dynamics in a system of people/functions (a family, a care network around a patient on a micro level and stakeholder setups on a macro level), anchored by brief personas as actors in the dynamic (see fig. 1, bottom right for an example).

In identifying the dominant patterns, we adapt a systemic phenomenological approach (Hellinger et al, 1998; Stam, 2012), using constellations to identify and manifest hidden dynamics. For more information on constellations and its use in systemic design see our contribution to RDS6 (Van der Lugt, 2017).

Case example in healthcare: active after stroke

We applied socionas as a guiding principle in a project on stimulating stroke patients to stay active after suffering a stroke.

Research indicated that self-reporting of amounts of movement does not provide enough and accurate feedback. A very sensitive motion sensor can give this feedback to both patient and therapist. Technically pretty straightforward, but in what ways could this product service system be designed in such a way that it will stimulate movement over a long period of time (3-6 months)? A team of healthcare (stroke) researchers, physical therapists, engineers, behavioural scientists and product- and interaction designers engaged in a co-design project in order to develop the product-service system

(see fig. 2).

Because the dynamics between patient, physio therapist and primary care giver(s) appeared to dominate the recovery trajectory, we developed first a variety of personas of these three roles and then combined these into recurrent pattern dynamics. This led to a series of 5 socionas that were used

throughout the design process.

A case exaple in sustainability: creative producers

A second case in which we used socionas concerns energy transition: The Creative Producers project.

In order to obtain information about the ambitions of residents regarding energy transition and their knowledge, needs and willingness to invest in their home it is important to know them and their social networks. By mapping this for a number of representative networks in the neighborhood, you gain more insight into the situation and you can determine strategies to start energy transition at a micro level.

At a macro level it is even a challenge to start a project in a municipality. Determine the necessary stakeholders whom all in their own expertise may or may not be involved, while struggling to manage interest, needs and everyone’s role in the project. The sociona can also be used in these situations to map the network system of representative stakeholders. Again, a person is not exchangeable; due to someone’s role, interests or character, other relationships and interactions may arise that may or may not benefit the project. A few citations from a participant can clarify this:

“It has to do with personalities. A person from a residents’ collective was very open and who welcomed us immediately. This influenced the success of the project”.

“There was a very involved alderman who could talk to the residents in a human way and was very confident at the same time”.

“At Alliander a person had lost the urgency and drive within the project, this caused difficulties. Only when a new person was put on the job, is resolved.“

In the Creative Producers project we used the socionas tool in a session with social designers who were responsible for the human side of energy transition. The designers were able to visualize dynamics with simple persona cards (see figure 3).

Interesting was that each designer used it differently (see figure 4). One more at micro level, the other more at macro level. Both immediately led to insights of system dynamics and generated inspiration for intervention strategies.

Visualize dynamics

To support the designers in focusing on the dynamics rather than the individual it can be helpful to visualize the socionas. On the basis of the example below it becomes clear how dynamics in a sociona can be made visual.

“Patient Alex (78 years old) had suffered from a stroke a few years ago. He has been very confused since then. He regularly visits the physiotherapist (Charlie, 38) who gives him all sorts of instructions that he needs to be more active. His wife Eva (71 years old) is a caregiver, Alex likes that. Eva is very protective; at home she takes on all the tasks. “You just sit down, I’ll make you a cup of tea”. When Alex comes back, therapist Charlie can see immediately, Alex didn’t do well at home. “Yes, of course you did not do all those exercises, I can see that right away.” Charlie tries to push Alex, but also tries to help by informing him simple tasks that make him more active, such as taking the mail out of the mailbox, climbing stairs or do some grocery shopping. Alex nods in agreement. At home, however, a completely different situation arises. Eva takes over all tasks right away. When Alex starts about what the physio said, Eva says: “But that does not work at all, what if you fall … I will not be able to catch you.”

Alex does not even start talking about it anymore, it is not worth the hassle. Besides that, he also likes to be cared for.”

Figure 5 shows the current group more or less “static” dynamics. Working towards a more dynamic attitude or introducing a fourth actor (the latter can be a person, but also an intervention), as can be seen in figure 6.

Discussion of the results

Constructing the socionas together in the ACTS case functioned as a boundary event (Stompff, 2012) in which collective sensemaking lead to socionas, which then functioned as boundary objects throughout the design and development process. Both designers and healthcare professionals were able to keep referring to these dynamics as a reference point whilst designing and developing prototypes.

The approach fit both the task at hand and the way both designers and healthcare workers approached the challenge. Play-acting enabled them to share their experience, to empathize and ideate. The socionas connected these experiences with literature research and stories of patients. Within the co-design process, being aware of the dynamics between patient, therapist and caregiver and making this tangible was a very helpful tool for the development of the intervention.

In the Creative Producers project, there was limited time, the tool was only used with the designers themselves. Involving the persons in question in the development could be very valuable. However, at these complex situations, a large number of personas leads to a vast number of socionas, which becomes too complex to grasp. Also, in the level of socionas it is important to stay aware of the prototypical nature, being fully aware that you will not be able to represent all dynamics. How to describe the most striking or persistent ones? A final question is how to keep the socionas even more ‘alive’ and work with them structurally throughout the design process. How to sense variations in system dynamics and how to allow socionas more ‘stage presence’ in the co-design process.

| Item Type: | Conference/Workshop Item (Paper) |

|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Keywords: | Co-design, Co-creation sessions, Personas, socionas, Systemic design, Systemic phenomenological, Approach, Design for healthcare |

| Related URLs: | |

| Date Deposited: | 24 Jul 2019 13:10 |

| Last Modified: | 20 Dec 2021 16:07 |

| URI: | https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/2762 |

Actions (login required)

|

Edit View |

Lists

Lists Lists

Lists