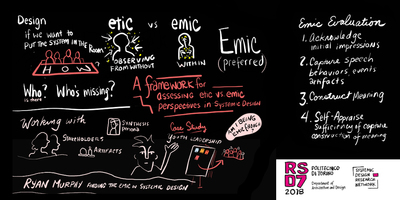

Finding the emic in systemic design: Towards systemic ethnography

Murphy, Ryan J. A. (2018) Finding the emic in systemic design: Towards systemic ethnography. In: Proceedings of RSD7, Relating Systems Thinking and Design 7, 23-26 Oct 2018, Turin, Italy.

Preview |

Text

Murphy_Emic_2018.pdf Download (1MB) | Preview |

Preview |

Text

Murphy_Emic_Slides_2018.pdf Download (6MB) | Preview |

![Murphy_Emic_MM_2018.jpg [thumbnail of Murphy_Emic_MM_2018.jpg]](https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/2750/3.hassmallThumbnailVersion/Murphy_Emic_MM_2018.jpg)  Preview |

Image

Murphy_Emic_MM_2018.jpg Download (277kB) | Preview |

Abstract

An under-emphasized but crucial variable of success in systemic design is the perspective through which a problem system is understood and from which interventions are conceptualized and implemented. While rooted in design (a consciously empathetic discipline; cf. Kimbell, 2011), it is easy for systemic designers to use research practices that may fail to capture and use the perspectives of their stakeholders. ftese approaches risk misrepresenting the stakeholders who contribute to projects and, in turn, they are a danger to the potential impact of these mis-researched problem systems. In this research, I propose an assessment framework to check whether a project effectively deploys research tools and processes that strengthen stakeholders’ perspectives, and I provide a proof of concept of this framework in use through hermeneutic case study analysis.

Systemic design processes that are not executed with the direct and explicit engagement of stakeholders—to the extent of achieving an emic (from within) understanding of the system—may be flawed at their foundation. By fostering recognition of the importance of an emic perspective, and by providing a framework of principles, practices, and processes to accomplish systemic design with this perspective, I hope to ensure that systemic design processes are as accurate and valid as possible with respect to the stakeholders of the system.

ftis is not to suggest that systemic design practice is “too etic” (from outside). In fact, with roots in design, systemic design is often deliberately emic. Systemic designers make use of designerly tools that help the researcher to build empathy with system stakeholders (e.g., soft systems methodology, critical systems heuristics, appreciative inquiry; Jones, 2014). ftey often seek to engage stakeholders in the systemic design process and include reflective analysis of what has been learned in order to assess where deeper engagement with the system is required (Ryan, 2014). ftat said, with the advent of crowdsourcing (the facilitated involvement of the general public in problem solving, usually using online tools; Lukyanenko & Parsons, 2012) and data science (the use of computational tools to analyze and understand large quantities of data; Šćepanović, 2018), data-driven methods may increasingly influence systemic design practice. One recent example sought input from hundreds of people to identify opportunities for change in Canadian post-secondary systems through an iterative online survey (Second Muse, Intel, & Vibrant Data, 2016). ftis data-driven direction is a powerful opportunity, of course, but it underscores the need to develop principles and best practices for assessing and supporting emic understanding as we gain more data from these tools.

In the first phase of this research, I look to the principles and theorists of ethnography to develop a framework for assessing the emic/etic perspective of a given research project. Namely, Geertz’ “ftick Description: Toward an Interpretive fteory of Culture” (found in The Interpretation of Cultures, 1973, chapter 1) provides a foundation for the process of emic research in the form of four iterative steps: (1) acknowledge initial impressions; (2) capture speech, behaviours, events, and artifacts; (3) construct meaning; and (4) self-appraise sufficiency of capture and construction of meaning. Meanwhile, Creswell and Miller (2000) provide a set of five procedural principles for emic validity: (1) triangulation; (2) disconfirming evidence; (3) prolonged engagement; (4) member checking and collaboration; and (5) researcher reflexivity. Taken together, I generate a critical research framework which can be used to assess a given research project’s emic/etic perspective.

In the second phase, I provide a proof-of-concept of this framework (and its theoretical underpinnings) via a case-based assessment of three systemic design projects. Case studies provide an effective venue for learning about the context- dependent manifestations of the phenomena being studied (Flyvbjerg, 2006). One of these case studies is one I have developed through my experience in participating and contributing to the development of the Canadian National Youth Leadership and Innovation Strategy framework, which convened hundreds of youth and youth-serving organizations in order to understand the youth leadership and innovation system in Canada (MaRS Studio Y, 2017). fte second and third case studies are those profiled by Ryan and Leung (2014). In each case, I use identify phenomena representing the practice of emic (or etic) understanding in the research orientation of the work, as acknowledged by the above framework. I examine the step-by-step procedure and any associated notes about the experience of the researchers and participants involved. In each step or experience, I look for evidence of the four steps of emic understanding or the six techniques of emic validation reported above.

In order to interpret and analyze the chosen case studies, I turn to the methodology of phenomenological hermeneutics (Eberle, 2014, p. 196; cf. Wernet, 2014). Phenomenological hermeneutics are appropriate as I have access to the described phenomena of the systemic design projects captured by the chosen cases, but these phenomena are not explicitly captured with reference to emic or etic perspectives—thus some construction of the inherent emic or etic data is necessary in order to make judgments about the perspectives found in the projects.

ftis hermeneutical analysis provides comparative evidence for the emic and etic perspectives used by the researchers in each case. It becomes possible to contrast and critique the principles, practices, and processes employed in each project in order to make a judgment about the project’s resulting emic/etic orientation. From these analyses, a metaphor emerges. Systemic design projects with etic orientations adopt an intensivist approach. Akin to intensive care in medicine, the systemic designers attempt to artificially suspend a system in a room. (Consider board room systems mapping as a trivial example of this practice.) Attempts are made to “get the whole system in the room”, but the system is therefore removed from its context. fte status of inaccessible elements of the system are guessed at and assumed, while other elements are placed in stasis and augmented by facilitation and technology. fte resulting interventions are spun up in this artificial space, but implemented in the system’s context—the systemic design team simply hopes that their assumptions hold and that the artificial suspension didn’t cause too much damage. System design projects with an emic orientation adopt an extensivist approach. fte designers themselves extend into the system. ftey sit with it for a while in order to acclimatize to its culture and learn its patterns. ftey interact with stakeholders and phenomena in context and capture these interactions as they are, as an ethnographer would. fte interventions they develop are (co-) created in place, built into the system’s real networks and activities.

Of course, the challenge with these dueling approaches is that there are important trade-offs. fte extensivist approach takes time and personal investment. What’s more, the intensivist approach can have other valuable outputs: stakeholders of a system see one another and the parts of the system they interact with as a cohesive whole. fte result of this analysis, then, is not an obvious set of best practices. Instead, the emic/etic assessment framework can be used to judge how a research project effectively captures the perspectives of its stakeholders. It breaks down a project into components, each of which provides an intervention point for enhanced emic understanding. Finally, it provokes a reflective conversation, forcing us to ask ourselves where we can do better.

| Item Type: | Conference/Workshop Item (Paper) |

|---|---|

| Uncontrolled Keywords: | Emic, Etic, Ethnography, Systemic design, Perspectives, Frameworks, Case study, Theory |

| Related URLs: | |

| Date Deposited: | 17 Jul 2019 18:04 |

| Last Modified: | 20 Dec 2021 16:08 |

| URI: | https://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/2750 |

Actions (login required)

|

Edit View |

Tools

Tools Tools

Tools